“Our world is going digital. Our day-to-day lives are more connected. There is a democratisation of online access and use. In this context, it’s becoming increasingly important to have a secure, authentic and verifiable digital identity with a user-centric approach and full protection of citizens’ personal data…” extract from the EU Digital Identity website.

The World Economic Forum sets up a digital identification system

In 2022, the World Economic Forum published a proposal for a large-scale digital identification system that will collect as much data as possible on individuals and then use this data to determine their level of access to various services. This digital ID proposal is presented in a report entitled “Advancing Digital Agency: The Power of Data Intermediaries“, and builds on a digital ID framework previously published by the World Economic Forum.

As part of this, the World Economic Forum proposes collecting data on many aspects of people’s “daily lives” through their devices, telecoms networks and third-party service providers. The World Economic Forum suggests that this data collection system would enable a digital ID card to collect data on people’s online behavior, purchase history, network usage, credit history, biometric data, names, national ID numbers, medical history, travel, social accounts, e-government accounts, bank accounts, energy consumption, health statistics, education, etc.

Once the digital ID has access to this huge set of highly personal data, the World Economic Forum proposes using it to decide whether users are allowed to “own and use devices”, “open bank accounts”, “carry out online financial transactions”, “carry out commercial transactions”, “access insurance, treatment”, “book travel”, “pass border controls between countries or regions”, “access third-party services that rely on social media connections”, “declare taxes, vote, collect benefits”.

A digital identity for every European

In 2014, the Electronic Identification and Trust Services Regulation (eIDAS Regulation) obliged EU member states to establish national e-ID schemes that meet certain technical and security standards. These national schemes are then connected, enabling citizens to use their national e-ID card to access online services in other EU countries.

In 2021, the Commission put forward a proposal, building on the eIDAS framework, to enable at least 80% of citizens to use a digital identity to access key public services across EU borders by 2030.

What is it used for?

With European Digital Identity Portfolios, citizens throughout the EU will be able to establish their identity if needed to access online services, share digital documents or simply prove a specific personal attribute, such as age, without revealing their full identity or other personal data. Citizens will at all times have full control over the data they share and the recipients of that data.

The EU digital identity can be used in a wide range of cases, for example:

- use public services, such as requesting a birth certificate or medical certificate, or reporting a change of address

- open a bank account

- complete a tax return

- enroll at a university in your home country or in another member state

- keep a medical prescription that can be used anywhere in Europe

- prove your age

- rent a car with a digital driving license

- check in at the start of a hotel stay.

Using the EU’s digital identity: the example of a bank loan application

Thanks to the EU digital identity, the user will only need to select the necessary documents, stored locally in their digital wallet, to respond to the bank’s requests. Verifiable digital documents will then be created and sent securely to the bank, which will verify them and then continue with the application process.

Transposition in France with France Identité numérique

As part of the European Commission’s work on digital identity, the ANTS (Agence nationale des titres sécurisé) is leading a consortium, called POTENTIAL, of 148 participants (public and private) from 19 EU member states.

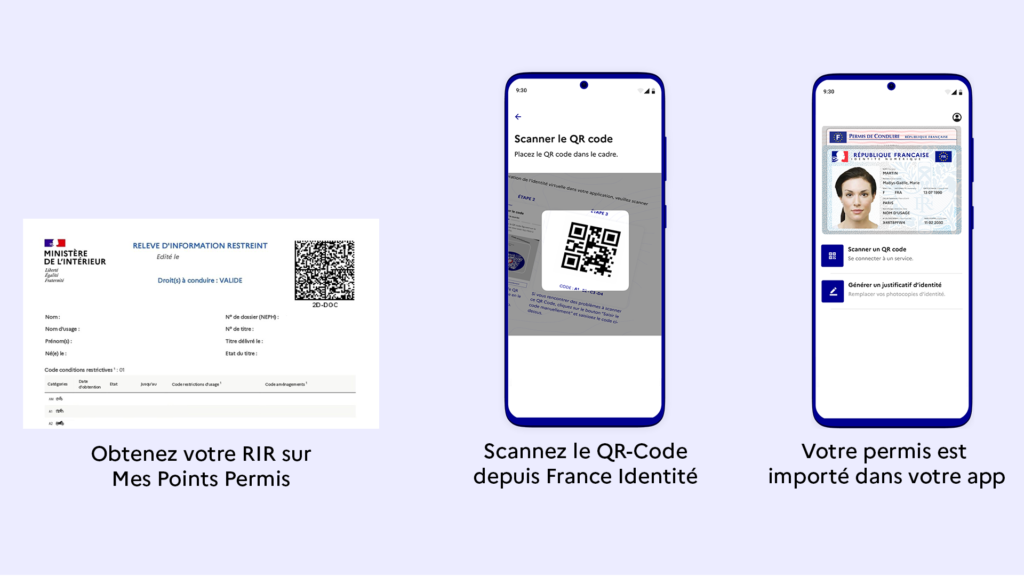

This service is the digital extension of the identity card. This is a description of the France Identité application. In February 2024, the driving license was integrated into the French application.

Since its launch, security has been at the heart of the France Identité numérique program. Several audits have been carried out on applications and the back-end. A private bug bounty was launched in June 2022, revealing a number of flaws. For the program’s security and transparency, a new audit was launched during a public bug bounty of this centralized application on February 28, 2024.

FranceConnect is the French government’s solution for connecting to online services and procedures. On a site featuring the FranceConnect button, instead of creating an account and having to remember an additional password, you can log in using one of the six options FranceConnect offers via an account that a French citizen already has: impots.gouv.fr, ameli.fr, Identité Numérique La Poste, Mutualité sociale agricole msa.fr, and Yris application developed by ARIADNEXT, acquired by IDnow.

Transposition to Italy: Smart Citizen Wallet in Rome and Bologna

Since 2022, for example, the municipalities of Rome and Bologna in Italy have been trialling social credit initiatives, which are incentive-based and optional, aimed at rewarding behavior deemed “virtuous” in terms of sustainable development via the “Smart Citizen Wallet” application.

In Rome, it “encourages virtuous behaviors implemented by city users, aimed at improving the city’s environmental, social and economic sustainability”. For the “virtuous” citizen, “points” are “converted into rewards (sustainable goods and/or services) offered by the Capital of Rome and its partners”.

In Bologna, the initiative, which is also optional, “aims to reward those who, for example, sort waste properly or use public transport and avoid fines”.

According to local newspaper Corriere di Bologna, which described the concept as “similar to a collection of supermarket points“

Digital identity in China

China’s social credit system is based on digital identity, for which forms of AI are used, such as computer vision. Facial recognition is used to identify pedestrians in certain cities. The Chinese regime initially preferred incentives to coercion.

The idea of social credit was born in 2007, and plans were announced by the government in 2014 as a voluntary system. But there’s a difference between the government’s official system and the companies’ private versions, although the latter’s rating system, which includes buying habits and friendships, is often confused with the former.

Rights and duties: “Promoting virtuous human behavior and trust”

China’s social credit system extends this idea to all aspects of life, judging citizens’ behavior and reliability. If you’re caught speeding, if you don’t pay a court bill, if you play your music too loudly on the train, you can lose certain rights, such as booking a flight or a train ticket.

There are incentives to participate and disincentives to non-participation.

Social credit is a technological means of linking political power to social and economic development that has been discussed in the country since the 1980s. It is an automation of Chairman Mao’s mass line, a term that describes the way in which party leaders shape and manage society.

Social credit at government level

The aim is for the government system to extend to the whole country, for companies to receive a “unified social credit code” and citizens an identity number, all linked to a permanent file.

If a citizen is included on the list of dishonest people liable to be punished by the Supreme People’s Court, he or she could be “disqualified” from buying a plane ticket and banned from traveling on certain rail lines, buying real estate or taking out a loan.

Social credit at local level

One city in Shandong province, Rongcheng, gives all its residents 1,000 points to start with. The authorities deduct bad behavior, such as traffic violations, and add points for good behavior, such as donations to charity.

Although this varies from program to program, in some local pilot projects, a positive score means discounts and benefits, such as simplified administrative procedures. If you have a poor rating, you risk incurring additional red tape or costs.

There is as yet no single social credit system. Instead, local governments have their own social registration systems that operate differently, while unofficial private versions are run by companies such as Ant Financial’s Zhima Credit (Sesame Credit). Ant Financial is the payment company spun off from Alibaba.

Social credit for private companies

Private projects such as Sesame Credit collect all kinds of data on their 400 million customers, from how much time they spend playing video games (which is bad) to whether they are parents (which is good). This data can be shared with other companies.

Systems use purchasing habits, among other data, to establish credit-type scores, based on voluntary membership. Data collected by private companies is likely to be recovered by public authorities in the future, and some of it is already being used in government trials.

Chinese social credit coupled with digital product passport

Chinese society is plagued by trust issues, from food quality and pollution scandals to employees failing to pay their salaries. The system can also be used to enforce vague laws such as endangering national security or unity. This can include food safety and product quality, major issues in the country.

Conclusion

China’s social credit system is developing, but it’s just one element in the country’s surveillance state. In addition to strict controls on available web content, via the country’s national firewall, social media are monitored and censored.

In the name of trust and integrity, those deemed trustworthy are rewarded, those deemed untrustworthy are punished. Moral principles mingle with legal norms, while the floating concept of “trust” provides fertile ground for the arbitrary expression of power.

In December 2020, 80% of China’s territories, i.e. over one billion people, are affected by various social rating measures. However, in November 2022, there is no centrally-assigned social rating for each individual.