In the ever-changing world of social media, an exciting new development has emerged: virtual influencers and AI-created social media personalities. These computer-generated personalities are grabbing people’s attention all over the world and completely changing the way brands connect with their customers. In this article, we’ll look at the interesting aspects of virtual influencers and AI-generated personalities. We’ll see how they’re changing the game and how they can help your business grow.

Virtual influencers are like digital characters. They are not real people, but are created using computer technology. These characters can look like humans or any fictional character, and they have their own personality and style, which can be trained using generative AI. People follow them on social media, like Instagram and YouTube, even though they know they’re not real. It’s like following a character in a movie or game. These virtual influencers share posts, give fashion advice and even promote products.

AI-generated social media personalities are also changing things. Using Generative AI, it can create content, like posts and videos, just like a human would. These AI personalities learn from what’s popular on the internet and then make their own posts from trending topics. People might not even realise that a human didn’t create the content! This is a big deal for businesses. These virtual influencers and AI personalities can reach a lot of people, and companies are starting to see that they can use them to advertise their products. It’s a new way of marketing that’s becoming more and more integrated. So, let’s explore this exciting digital world and see how it’s changing business as we know it.

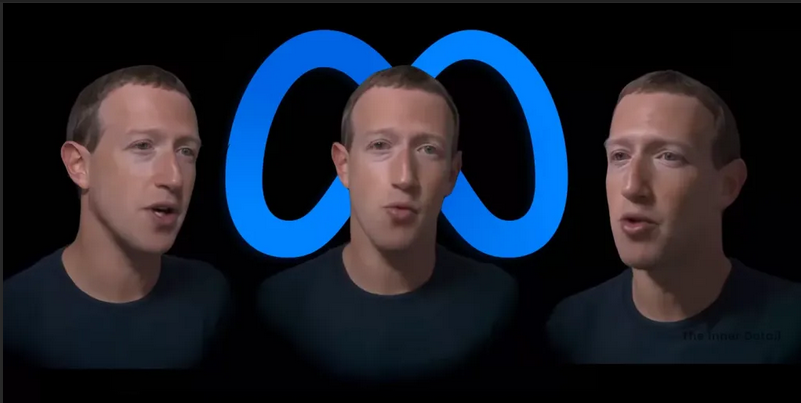

Meataverse – avatars in the look of public stars by Meta

At Meta’s annual event, Mark Zuckerberg announced the creation of virtual assistants based on real people, thanks to artificial intelligence. This raises legal questions regarding contracts, personal data and the regulation of these avatars, both for living personalities and the deceased. These developments could have implications in Europe, underlining the need for regulation adapted to artificial intelligence in this constantly evolving field.

On September 27, 2023, at the company’s annual Meta event, “Connect”, Mark Zuckerberg announced that the company was developing virtual personalities using AI to recreate virtual assistants with the characteristics of popular personalities. The aim is to enable users, via a messaging service as well as virtual reality, to chat with and seek advice from public figures such as Paris Hilton, Tom Brady, Snoop Dog and Kendall Jenner, among others.

For the time being, we’re only talking about projects involving American celebrities, but there’s no doubt that, should these technologies prove commercially successful on the other side of the Atlantic, they will be exported to Europe. What’s more, it’s also likely that a French user would prefer to chat with a digital copy of Antoine Dupont, Pierre Niney or Léna Situations… So, leaving American law to one side, it’s worth asking how our positive law applies to such digital upheavals. The adaptability of personal data law, personal rights law and contract law to such situations must be questioned today.

Digital reproduction of deceased personalities

A more worrying point, however, raised by Meta’s founder, concerns the creation of digital avatars of deceased people. It is claimed that we will be able to chat with virtual avatars that take on the personalities of deceased loved ones. In addition to the philosophical and psychological questions raised by this scenario, worthy of a dystopian fiction, there are many legal issues.

Mark Zuckerberg has announced that such a service could be used to dialogue with digital copies of deceased loved ones. A second question seems to arise with regard to beings who no longer enjoy legal personality and therefore the capacity to consent to such treatments.

Meta’s ads refer to collaborations with celebrities. It is possible to deduce that there is a contractual relationship between the individuals and the company with regard to their digital reproduction. It therefore appears that the path to be primarily explored in order to address these issues must be contractual. Artificial intelligence, for example, makes it possible to reproduce the voice of certain personalities, often without consent. In addition to questions about the legal status of the voice (emanation of the body? personality? personal data? etc.), we need to consider the consequences of malicious and unforeseen use: what about using the voice to make a statement that runs counter to the thoughts of its original sender?