We are witnessing a process of profound transformation that is rapidly taking shape, with technological acceleration as one of the main driving forces.

Mechanical production, marked by the invention of the steam engine and the construction of the railroad, was the first step in the industrial revolution that had just begun in the 18th century. Subsequently, the advent of electricity and the assembly line gave rise to mass production, the second major link in the industrial revolution. Finally, the development of computers and the Internet in the 1960s gave rise to what is known as the third industrial revolution.

The current technological revolution is characterized first and foremost by the speed of innovation and dissemination. Unlike previous revolutions, change is no longer linear but exponential. The possibility of having millions of people connected via the Internet has led to unprecedented data processing and storage capacity. As a result, each new technology in turn spawns a newer, more powerful one.

A second characteristic is the breadth and depth of change: many radical changes are taking place simultaneously. The interaction of various disciplines and discoveries of all kinds have ceased to be the stuff of fiction and have become tangible realities. Today, the fusion of technologies encompasses diverse fields: autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, advanced robotics, the Internet of Things, AI.

Finally, a third characteristic is linked to the profound transformation generated by the impact of these new developments. Not only are we witnessing the creation of new business models and the overhaul of production, consumption and transport systems, but, at a societal level, a paradigm shift is taking place in the way we communicate, express ourselves, inform and entertain ourselves, and even in the way our governments and various political domains are managed.

Democracy: the frontier between the ideal and the real

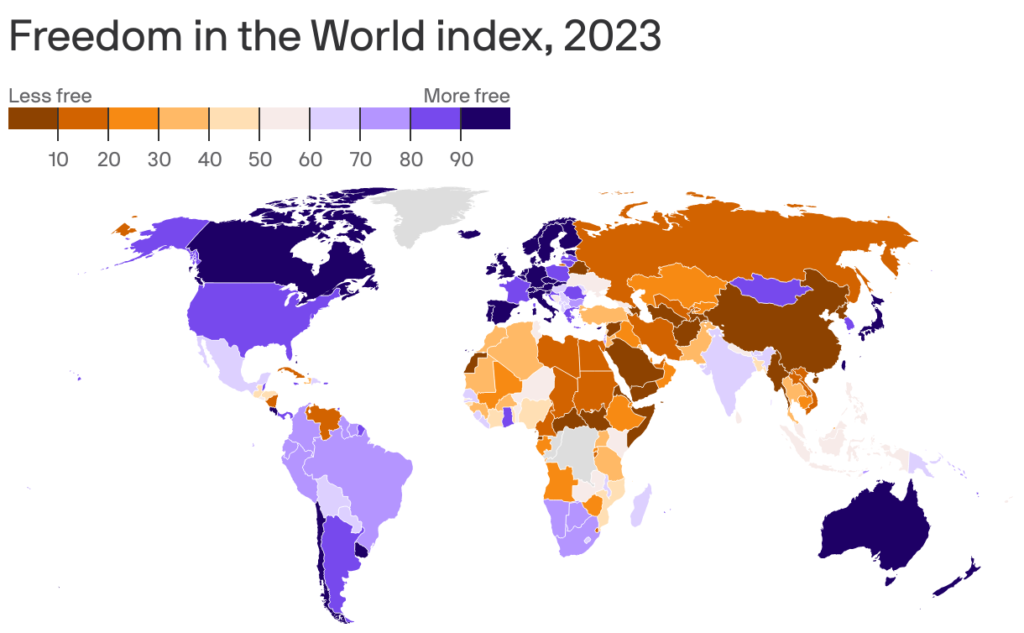

It is possible to identify multiple ways of defining and redefining this concept. In The Economist’s 2023 Democracy Index, only 24 of the 167 countries analyzed are considered « full democracies ».

As democracy, as a unit of analysis, developed, researchers began to ask new questions and use new variables that would make it possible to complexify and observe the various attributes of this « new phenomenon ».Despite the increase in standards and measurement tools, consensus on the conceptualization of democracy is far from being reached. Perhaps one of the keys lies, as Pierre Rosanvallon recently suggested, in the fact that: « Historically, democracy has always manifested itself as both a promise and a problem. The promise of a regime in line with society’s needs, based on the dual imperatives of equality and autonomy. The problem of a reality that is often far from satisfying these noble ideals ». Since democracy is a human construct, full of expectations and disappointments, determining its true scope is no easy task.

Some of the world’s most eminent political scientists have fought this battle. Norberto Bobbio drew attention to the false promises of democracy, highlighting structural shortcomings in terms of participation, representation, power and transparency.Giovanni Sartori drew a distinction between real democracies, as they exist in reality, and ideal democracies, as we would like them to be. Even more radically, Robert Dahl argued that democracy is not possible, coining the term polyarchy.

Four challenges for representative democracy

In What to expect from Democracy. Limits and Possibilities of Autonomy, Adam Przeworski attempted to free real democracies from the false expectations of the autonomy ideal. According to the author, representative democracy has failed to resolve, and is unlikely to resolve, four challenges that even today continue to provoke widespread discontent.

Przeworski begins his analysis by exploring the controversial terrain of equality. In his view, one of the most incisive criticisms of democracy lies in its inability to generate socio-economic equality and, consequently, to forge a social situation where political equality coexists with social and economic inequality.

Nostalgia for effective participation is another problem that continues to afflict modern democracies. As Przeworski explains, although in representative democracies voters have real choices, they will never choose from all conceivable possibilities, since it is only possible to choose from the options on offer. What’s more, despite the diversity of options, no individual can propose an alternative to the one chosen.

A third limitation of democracy lies in the impossibility of ensuring perfect agentivity, i.e. guaranteeing that governments do what they are supposed to do: represent. Since, in modern democracies, voters delegate their interests to representatives, Przeworski explains, the latter are supposed to represent these interests effectively. But if we consider that representatives also have interests, the costs of agentivity are inevitable.

Finally, another challenge of democracy lies in the difficulty of balancing order and non-interference. According to the author, maximizing freedom while interfering as little as possible in private life and guaranteeing, at the same time, as much security as possible, « […] is not easy to solve and can never be solved once and for all ». Insofar as any legal order is a form of oppression, some people will have to live for some time under laws that don’t suit them.

Either liberal democracy is rebuilt, or the risks of new authoritarianism will become ever more frequent

Although debatable, Harari’s work is an important reference for anyone wishing to understand and critically analyze the impact of the current informational technological revolution on the political order constructed by the West over the last few decades. Technology continues to develop exponentially, while democracy seems, a priori, rather immobile and with little capacity to respond.

In its current form, democracy will not survive the fusion of biotechnology and infotechnology. Either it will succeed in reinventing itself in a radically new way, or humans will end up living in digital dictatorships.

Yuval Noah Harari, Author of Sapiens and Homo Deus: A Brief History of the Future

Our species, argues the author in Homo Sapiens (2014), has succeeded in dominating the planet thanks to its ability to construct narratives and cooperate on the basis of them flexibly and in large numbers. All large-scale human cooperation, Harari argues, is established on the basis of shared myths that exist only in the collective imagination: from the gods of antiquity to the modern ideal of democracy. For at least three centuries, Harari argues in Homo Deus (2015), our Western societies have been organized according to a narrative in which human experience is the supreme source of authority: humanism. Over time, the evolution of this narrative has split into three main branches: liberal humanism (democracy, human rights and the capitalist-socialist free market); socialist humanism (including communism); and evolutionary humanism (including fascism). Allied victory in the Second World War put an end to fascism and, with it, to evolutionary humanism, while Western victory in the Cold War put an end to socialist humanism. Since then, democracy, human rights and free-market capitalism seemed destined to endure indefinitely, as Francis Fukuyama put it in his famous and controversial « End of History ».

According to the author, the liberal narrative considers individual free will to be the most important value. Whereas in economic matters « the customer is right », in politics « the voter knows what he wants ». According to this view, « democracy assumes that human feelings reflect a mysterious and profound ‘free will’, which is the ultimate source of authority, and that while some people are more intelligent than others, all humans are equally free.

This assumption is currently the Achilles’ heel of liberal democracy. « Once someone […] has the technological ability to access and manipulate the human heart, democratic politics will turn into an emotional puppet show, » Harari asserts. The fact that voters can be manipulated is not a new concern. In an article written over half a century ago, Joseph Schumpeter, one of the precursors of democratic theory, argued that the information and arguments presented to voters are always in the service of a political intention.

Giovanni Sartori was equally skeptical when he wrote Homo videns. According to him, with the development of television, homo sapiens has entered a crisis, a crisis of loss of knowledge and the capacity to know. Permanent exposure to the bombardment of images has led to a loss of the capacity for abstraction and reasoning, producing an apathetic, manipulable being. Although the author concentrated his efforts on analyzing the impact of television, he also reflected on the future of an idea that, at the time of his analysis, was in its infancy: the Internet.

Despite the difficulties of establishing the degree of influence of the phenomenon, i.e. proving the extent of its influence, it is possible to highlight three empirical trends to reflect on the reasons for such an impact:

- our most mundane decisions, such as searching for information and discussing political issues, reveal a marked dependence on various types of AI, such as search engines and social networks

- as a result of the above, we transfer large volumes of personal information to third parties

- this information, in addition to being commercially and politically valuable, is concentrated within a small elite with the capacity to process it.

The rebellion of democracy

In a recent article entitled « Democracy needs rebellion », author Markus Pausch discusses the relevance and importance of resistance and rebellion in maintaining the spirit of democracy. By analyzing the works of French writer and essayist Albert Camus, rebellion emerges as an irreducible sphere of democracy, including several arguments in favor of a « theory of democracy as rebellion », which includes the « integral components of doubt, criticism, modesty and doubt ». The essential thing is the right to say no, the right to rebel against what we consider unjust, wrong or unethical. Revolt and rebellion are not revolutions; they do not follow a complete ideological program aimed at changing the world in a certain « meaningful » way or in a certain historical direction. Revolt and rebellion do not take up arms to fight for power or to bring down the enemy, except in cases of self-defense or resistance to occupation. Revolt and rebellion are more spontaneous and do not necessarily « lead to systematic democracy ». In a world interpreted as having no definitive meaning, the attitude of rebellion is a radical democratic value, complemented by dialogue and the awareness that one’s own beliefs or convictions may also be wrong.

Of course, in addition to freedom and the right to rebel, you need a certain awareness of disagreement, a rejection of the unjust and the will to act against it. When minds are hacked, it’s the ultimate peril of power, as subordinates fall in line with tyrants.

This should be our main concern, regarding AI, big data, networks, bioengineering and democracy, as Harari sums it up: « To put it very, very concisely, I think we’re entering the era of hacking human beings, not just hacking smartphones and bank accounts, but really hacking homo sapiens, which was impossible before. I mean, AI gives us the necessary computing power and biology gives us the necessary biological knowledge. When you combine the two, you get the ability to hack human beings and if you keep trying, and building society on 18th century philosophical ideas about the individual and free will and all that in a world where it’s technically possible to hack millions of people systematically, it’s just not going to work. And we need a new story…

How does democracy work in a world where someone understands the voter better than the voter understands himself?

Politics has entered an algorithmic phase, in which a large proportion of voters are seduced by messages tailored to their needs by technological systems that know them better than they know themselves. Behind these innovations lies a vision of the world that can be summed up as technoliberalism.

Technoliberalism is the predominant philosophy of Silicon Valley, which equates an updated version of classical economic liberalism with a new faith in the liberating potential of technology. Technolibertarian ontology consists in disqualifying human action in favor of a « computationally superior » being, writes Eric Sadin. The ultimate aim of this philosophy is to break free from the shackles of politics, and move towards human emancipation from the state, the political class and judicial norms.

To achieve this, it calls on a superior intelligent digital system, capable of constituting a kind of global collective consciousness endowed with the greatest autonomy and the ability to choose the best for humanity from a set of possible scenarios.

Although the polysemy of democracy is high, it can be summarized as a certain political regime that gives power to citizens because they have the right to choose their representatives and to be elected, in a social context of freedoms, with relatively autonomous individuals who believe they know or feel what they think is best, with political parties competing for their vote. For a democracy to function more or less well, there must first be, as Max Weber pointed out, a belief in the legitimacy of the institutional framework that guarantees it. Without this belief, it is impossible to maintain it. This is one of the main challenges facing democracy in the context of silicolonization.

While the concept of the silicolonization of the world may be attractive for explaining certain things, such as the fragility of nation-states, it’s important to note that nation-state affectation occurs when systems of government are open, as is the case with democracy. In closed political systems, by contrast, the logic seems to be the opposite: it serves to enable the autopoiesis of that same closed system, perfecting and expanding it. Democracy is in crisis. This is nothing new, but today it is aggravated by the impact of the voracity of the latest generation of information technologies. Despite its limitations, no political project to date has succeeded in simultaneously offering greater opportunities for participation, representation, freedom and equality.

Blind faith in « liberation technologies » and the trivialization of the negative effects of network abuse and « big data » have widened the gap. As several researchers have recognized, today’s democracies need new methodologies, new technologies, that enable them to protect themselves against the toxic combination of these factors.

Certain technologies – such as blockchain – offer the promise of empowerment and citizen emancipation, strengthening social ties in the same way as technologies that will be used to promote collective organization.