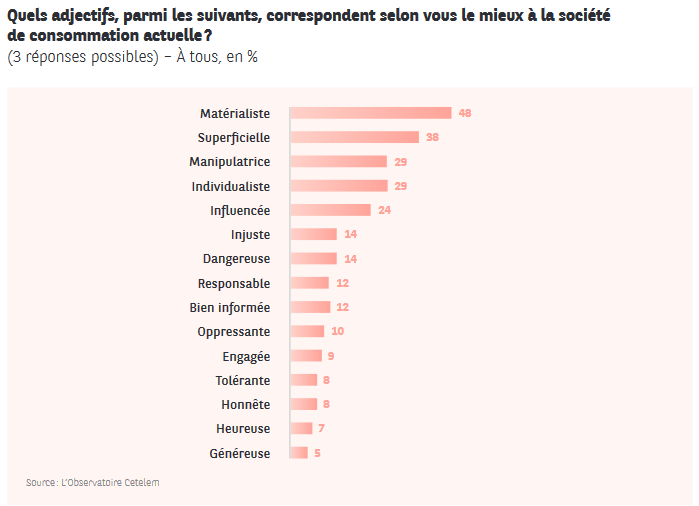

The golden age of euphoric, status-laden, carefree consumption, a symbol of improved living conditions and a sign of a society looking to the future with envy, now seems to be over.

After the acting consumer, driven by the quest for an offer that can be personalized, then the author consumer who wants to co-design with brands what they have in store for him/her, now comes the activist consumer, the ultimate figure of post-modern consumption.

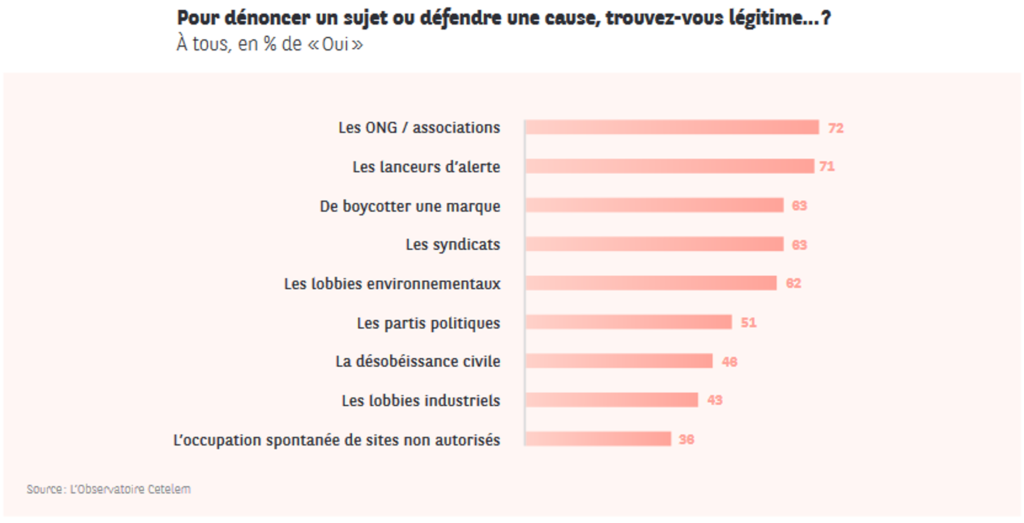

Long studied on the bangs of consumer resistance or responsibility, this activism is now considered an object of study in its own right. At the center of researchers’ attention are activist consumer movements, which either challenge the actions of marketers and their organizations, or mobilize to promote cultural change through consumption. In addition to politicized consumer movements, collective consumer activism can be described as “light” activism, far removed from the canonical model of political activism.

Whether politically committed or “light”, activism can be found in work on consumer movements carried out in different sectors and countries: from beverages such as beer in Denmark or cola in Germany, or video game downloads in Brazil, to food services in Finland, motorcycles in the USA, cinema in the UK and comics on a global level.

The consumer activist is first and foremost an activist. They want to take action, and consumption is their weapon. Act for their own, for others, for their environment and for their planet, which is also ours. To say that the activist consumer is determined is an understatement. Determined to change the current rules of the game rather than wait for the big night with its promises of a new world. Determined, too, to show that his generation is the first to be aware of the limits and dangers of the never-ending race for more.

The consumer activist is a committed consumer who wants his or her battles to be heard and recognized. Today, to act is to see oneself acting. This doesn’t mean militating against consumption, or denouncing it as we did fifty years ago, when its logic of limitless expansion was confronted for the first time by the economic crisis.

But to create the conditions for the emergence of a new form of consumption. More responsible, closer to one’s true desires than to the imperatives of permanent novelty, and driven by the idea of circulating goods so that everyone can enjoy them rather than accumulating them for the sole benefit of their own enjoyment.

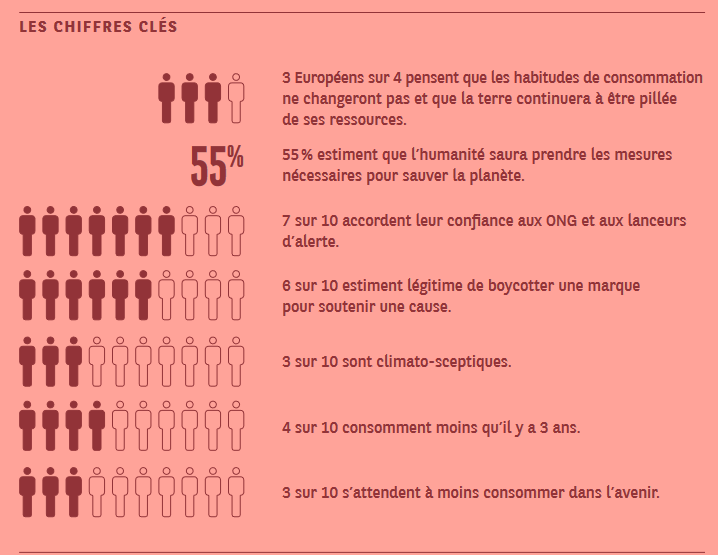

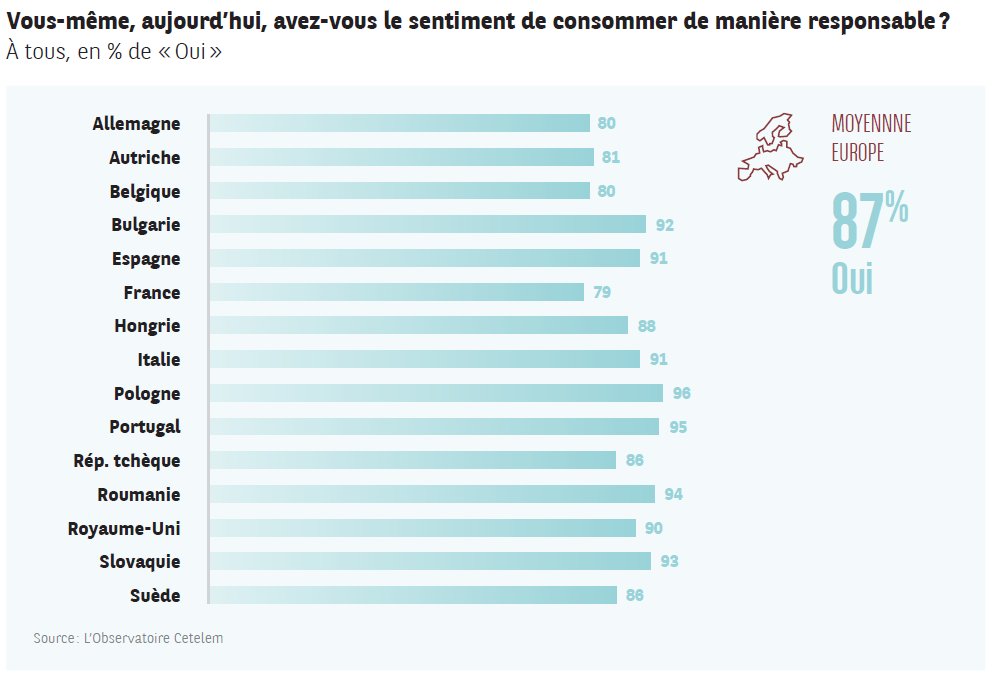

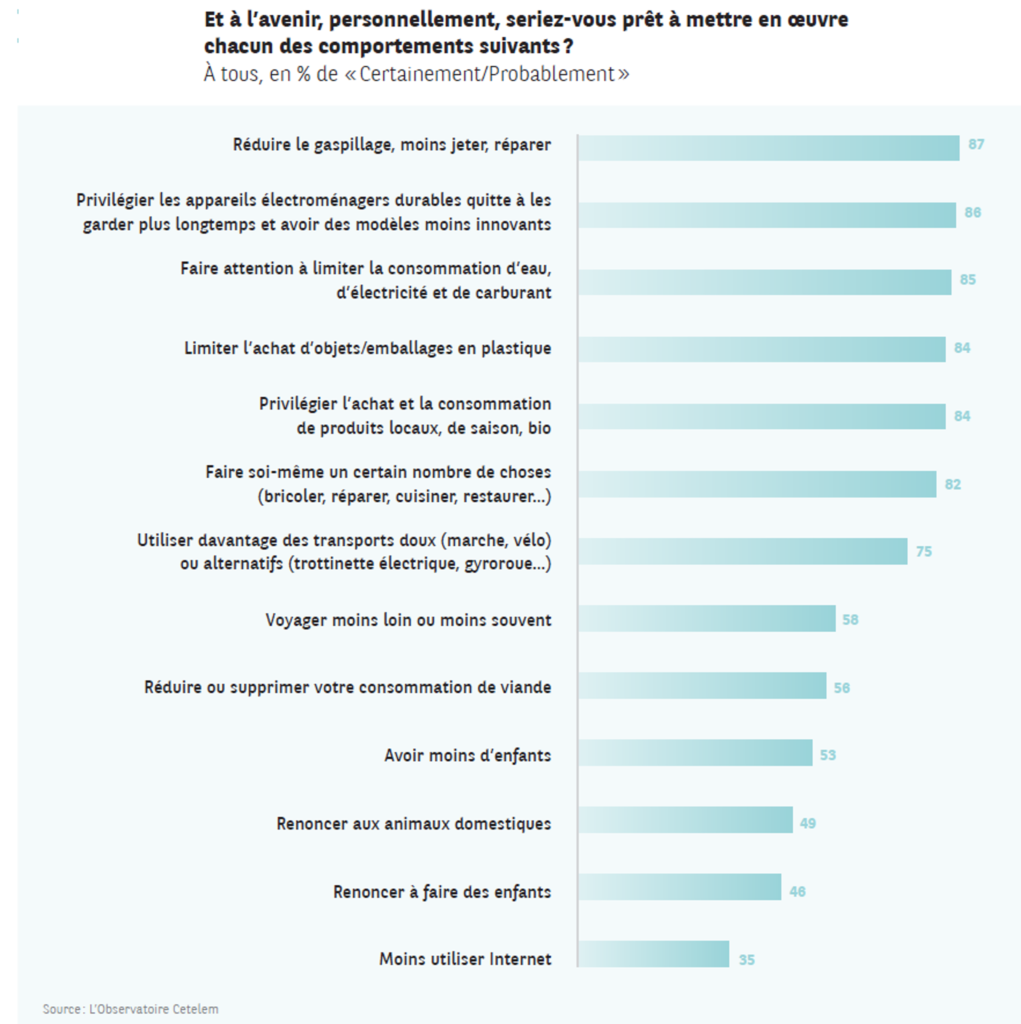

According to Europeans, this shift towards more responsible consumption is already taking place. 87% are already taking action. The Portuguese and Poles are the most resolute, while the French are relatively less assertive. Millennials are less numerous than seniors in highlighting this new state of mind. This is undoubtedly a more natural way of living and acting for a generation that has been aware of problems such as global warming since its origins.

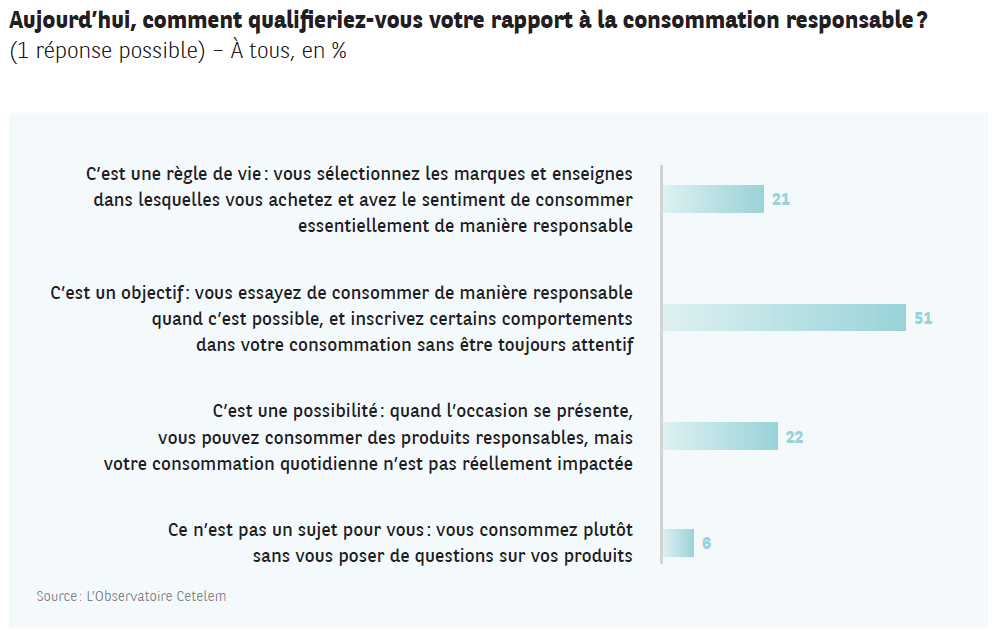

The markers of responsible consumption reinforce an activism that owes nothing to chance. For 51% of Europeans, it’s a goal and, better still, a rule of life for 21% of them. The Italians stand out in this respect (31%), while the Spanish and French are mobilized to make it a goal (59% and 55%). The Eastern European countries have the weakest convictions.

The desire to consume less is coupled with the desire to consume differently. This has given rise to a new central player on the consumer scene: the consumer activist. An activist consumer who commits himself individually, through concrete actions, to changing the face of consumption.

An activist consumer who wants to believe in global awareness, for the good of the community, preferably the one closest to him or her.

The consumer activist has not given up on consumption. They haven’t decided to resign themselves to it, by consuming less or giving up part of their pleasure, but to consume differently. Always criticized for its excesses and its tendency to activate desires that have never been asked for, consumption is now at the heart of change. It is through consumption that consumption will reinvent itself. It is through consumption that is more supportive, more responsible and more aware of the planet’s energy and ecological challenges that we may, perhaps, succeed in preserving it.

New consumer figures are emerging, driven by the desire to consume differently. Consuming to protect the environment and assert their citizenship. To consume without giving up, despite strained purchasing power. And even to consume without spending, the ultimate paradox and proof of the innovative state of consumerism today.

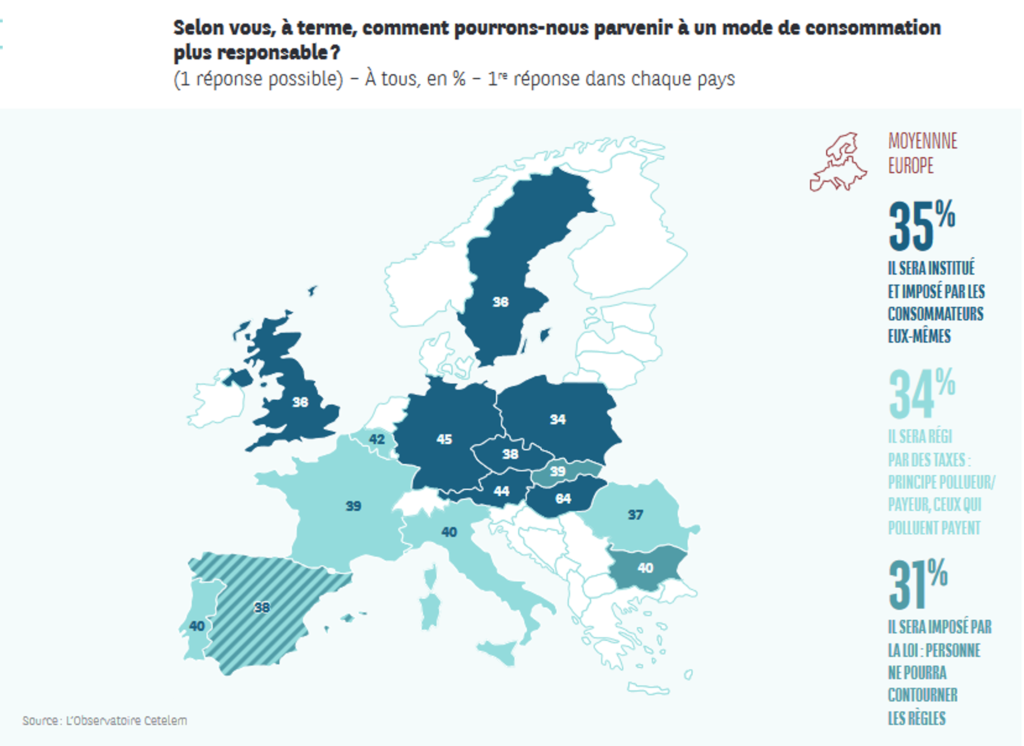

For 35% of Europeans, more responsible consumption will be imposed by consumers themselves. This “solution” is more popular than polluter-pays taxes or restrictive legislation (34% and 31%). Northern countries are the preferred destination for these new consumers, who are influencing the future of consumption.

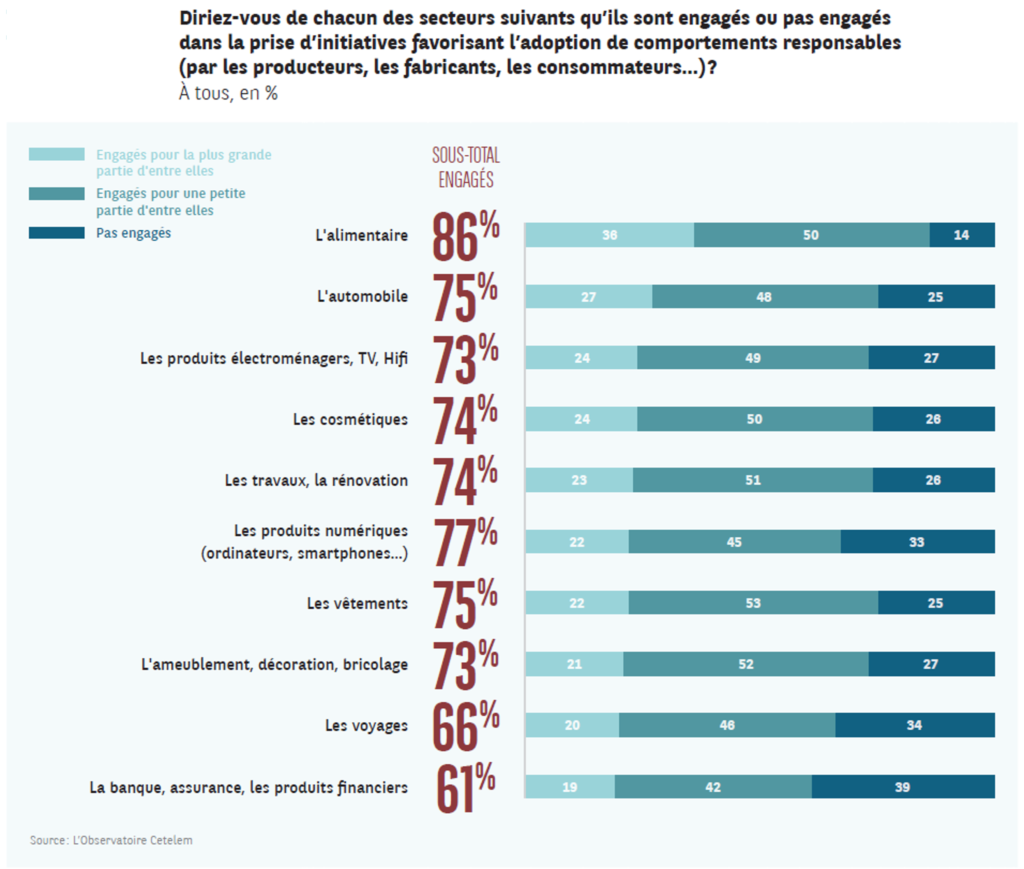

Europeans are positive about the commitment of different economic sectors to more responsible consumption). Far ahead of the others, the food sector received the highest rating (86%). This result is undoubtedly due to the greater visibility of organic and short-distance food products, supported by effective communication. The second place occupied by the automotive sector (75%) follows a similar logic. Brands’ efforts to develop hybrid and electric cars are being noticed, although they are not translating into significant sales. At the end of the ranking, travel (66%) is penalized by the transport it generates, while the world of finance is penalized by its immateriality.

Activism trends

Flygskam, or the “shame of flying”, is a phenomenon that’s just taking off. Originating in Sweden, it is beginning to spread throughout Europe and the United States. This preference for all means of transport other than air travel is having a direct impact on the Swedish air market: -6% on domestic traffic, -2% on international flights. If this phenomenon were to become more widespread, global traffic forecasts would be significantly affected.

Health is a key concern, especially when it comes to diet. After France and its 14 million users, the Yuka app is now enjoying success in Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, Luxembourg and the UK. The Nutri-Score nutrition labeling system, recommended in France since October 2017, has been mandatory in advertising since February 2019. Thirty-four major companies have committed to implementing it. It has also been chosen in Spain and Belgium. In the UK, a similar system is gradually being adopted by consumers. In Germany, some producers are interested in the system. Among the major European countries, Italy stands alone in its persistent refusal to adopt the system.

Major food groups are becoming aware that their customers’ tastes and expectations are changing. To better satisfy them, some, such as Coca-Cola, Kraft and Mondelez, have created dedicated incubators to invest in start-ups promoting the nutritional quality, naturalness or low environmental footprint of their products. Endowed with 200 million euros, Danone Manifesto Ventures plans to take stakes in around twenty companies. General Mills’ 301 Inc. has already invested in more than 10 start-ups in the United States.

Fast-fashion has lost its lustre. In France, volumes are down for the second year running. Geoff Rudell, analyst at Morgan Stanley, believes that the global apparel market has reached a ceiling and that its decline is structural. The cause is its ecological and social impact, which consumers are less and less willing to accept. Like slow-food and low-tech, slow-fashion is developing as a counterpoint to traditional consumer behavior. A way of being fashionable and consuming in a more informed way, consistent with the use of products, such as those proposed on SloWeAre, the reference platform for slow-fashion. In 2019, nearly half of all Europeans said they had purchased “respectful” fashion items, including recycled textiles, organic and second-hand products…

The 7th continent worries and frightens. These thousands of square kilometers of plastic waste drifting in the oceans are prompting consumers to change their practices and governments to take action. On June 12, 2019, the European directive banning the marketing of certain single-use plastic products was published. From July 3, 2021, straws, cotton buds, coffee stirrers, cutlery and plates will thus be completely banned in the European Union. Plastic bottles will have to contain at least 25% recycled plastic by 2025, 30% by 2030, and 90% of bottles will have to be recycled by 2029.

The second-hand market is booming. And within 10 years, it should even overtake the fast-fashion market. In France, it represents 50 billion euros, all sectors combined. The leader is the Leboncoin site, with 1 million daily ads and 28 million monthly visitors. Retailers are also getting in on the act, like Bocage, offering shoes that have already been worn, or Camaïeu, organizing a digital dress sale. 60% of French people said they had bought a second-hand product in 2019, compared with 47% ten years previously.

Even more than DIY (Do It Yourself), Makers are RIY (Repair It Yourself). New brands such as Ifixit and Spareka are helping consumers in the fight against programmed obsolescence to repair their electrical appliances. The European Commission has also taken up the issue. On October 1, 2019, it adopted a regulation on the reparability and recycling of household electrical appliances. As a result, spare parts for refrigerators will have to be available for at least 7 years, and 10 years for washing machines and dishwashers. Expected savings from all these measures: at least 150 euros per household per year, and the equivalent of one year’s Danish energy consumption by 2030.